How Were Paints Made For Van Gogh

Due west hen Vincent van Gogh got out of hospital in January 1889, with a white bandage roofing the place where his left ear had been, he immediately went back to work in his house adjacent to a buffet in the southern French boondocks of Arles. A still life he painted that calendar month looks similar a adamant endeavor to agree on to the things of this globe, to quell his inner turbulence by concentrating on the solid facts of his life. Around a sturdy wooden table he has laid out a symbolic array of the simple pillars of his existence. Iv onions. A medical cocky-aid book. A candle. The pipe and tobacco he found steadying. A letter from his blood brother Theo. A teapot. And one more than thing: a big, emptied canteen of absinthe.

Has he boozer the absinthe since leaving hospital? Does its emptiness represent a promise to swear off the stuff from now on?

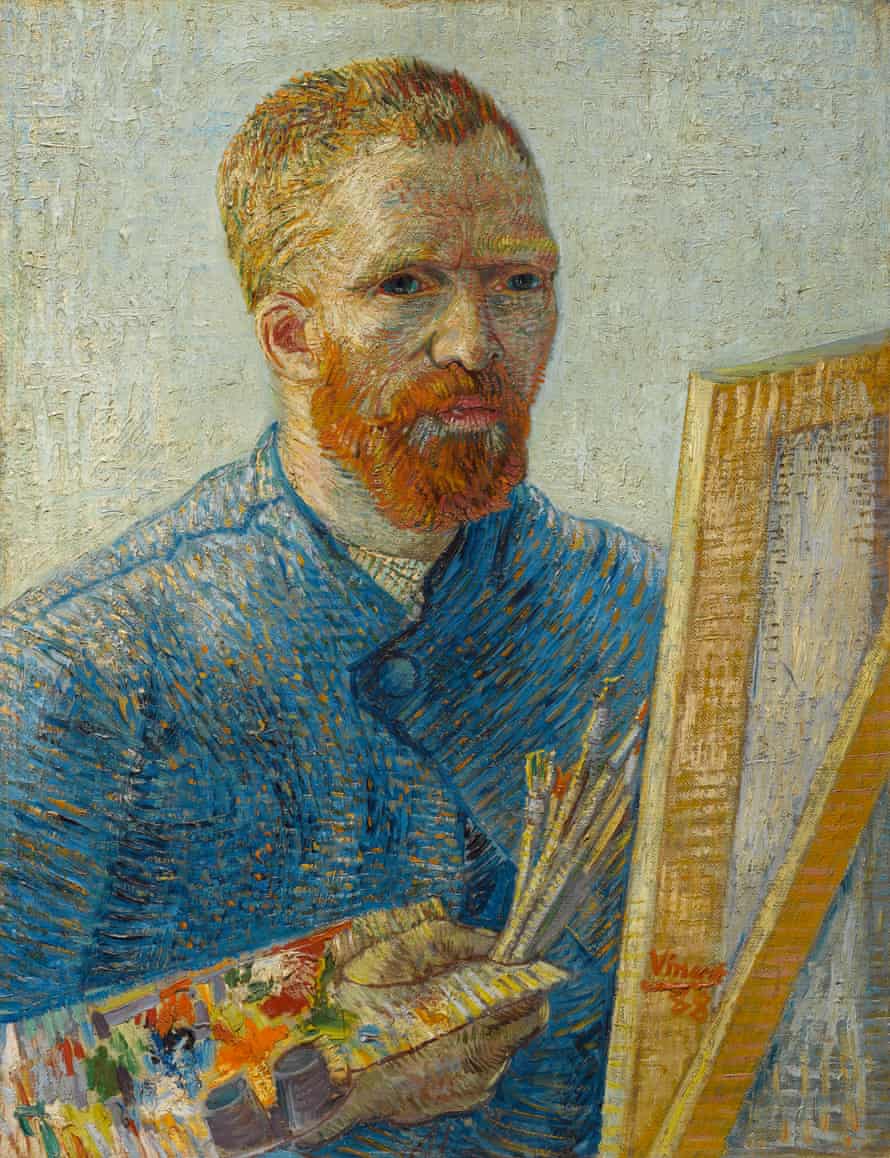

The showtime affair to be said about this painting is that it is revolutionary. It is a new kind of art. The very idea that a collection of objects, painted with fiery brushstrokes in heightened luminous colours, with ridges of thick impasto in some places and bare canvas in others, can reveal the state of someone'southward soul was utterly new. Van Gogh was its originator. In the months after this mostly self-taught Dutch artist in his mid 30s arrived in Arles in February 1888 he invented a new kind of fine art that would come up to exist called expressionism.

In the process he drove himself mad.

That probably sounds like a dangerously Romantic way of putting it to curators of On the Verge of Insanity: Van Gogh and His Illness, an exhibition at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. This sensational show – how strange to see the rusty gun, found in a field at Auvers-sur-Oise, that the museum is "80% sure" Van Gogh shot himself with, in 1890, at the age of only 37 – is total of fascinating documents that tell a sad story of a man struggling with his failing mental wellness until finally, in despair of e'er getting well or living independently, he chose suicide. Information technology presents a lucid narrative of the concluding phase of Van Gogh's life. Yet it is ultimately a pedantic and misleading exhibition whose pursuit of clinical accuracy misses the mystery of Van Gogh's life and art.

The straw man the curators want to tear downward is the myth that Van Gogh'due south genius lay in his "madness", that he painted in the fever of hallucinations and took inspiration from affliction. Information technology has been decades now since radical psychiatrists such as RD Laing celebrated mental disease equally a sane response to an insane society. My onetime Penguin copy of Michel Foucault's book Bailiwick and Punish has Van Gogh'southward painting of prisoners walking in a futile circle in a claustrophobic walled grand on its cover: he painted this in the aviary, based on a print of Newgate prison house by Gustav Doré that his blood brother sent him. The Doré is in this exhibition. In another book, Madness and Culture, Foucault contrasts the openness to madness that supposedly one time filled the earth with Bosch-like creativity with the modern world's castigating isolation and medicalisation of the "mad".

Van Gogh's expressionism became the best known avant-garde movement in northern Europe in the early 20th century and the image of his "madness" was deeply carved into information technology. When the German expressionist Ludwig Kirchner painted himself as a wounded soldier with a severed mitt in 1915 – his real injuries were mental, non physical – he drew on the legacy of Van Gogh's Cocky-Portrait with Bandaged Ear to create a study in shell shock. In 1922 the psychiatrist Hans Prinzhorn published The Art of the Insane, which features his collection of his patients' paintings and drawings, illustrating what he sees equally a unique form of creativity. His belief in the inventiveness of mental illness was clearly inspired by expressionism and its cult of madness that goes back to Van Gogh himself. Prinzhorn'due south ideas are still influential today in the booming world of "outsider fine art".

The Van Gogh Museum can't stand the notion of Vincent van Gogh as an outsider creative person. Its new exhibition is office of a longstanding struggle to free his paintings from such melodramatic views. For instance, information technology rejects what it sees as sensational interpretations of his 1890 painting Wheatfield with Crows: just because it was done near the stop of his life and has crows like vicious slashes of blackness cutting into the deep moisture blue of the sky, don't go thinking this is a confession of inner agony. In any case, as this exhibition shows, this disturbing piece of work was non Van Gogh'southward concluding painting, as information technology'south widely thought to exist. His real last canvas is on display: it is a tangled and dreamlike study of tree roots. The jagged strokes, expressive unreal colours – the tree roots are blue – and empty areas of sheet are just as suggestive equally those menacing crows. He left this painting unfinished when he killed himself.

When it comes to the cloth reality of Van Gogh'south last days, this exhibition is harrowing. Information technology even has a cartoon of him on his deathbed. His final alphabetic character, which Theo plant in his pocket, has stains on information technology which forensic scientists have not still been able to prove or disprove are blood.

Compelling evidence, just precise every bit the exhibition is most Van Gogh's decline – from cut off his ear to inbound an asylum to suicide – information technology ignores huge and haunting questions about how his troubled life shaped the greatness of his fine art.

You don't need to subscribe to the 1960s views of Laing or Foucault to think this exhibition medicalises Van Gogh's mental health too much. What it shows is perfectly accurate on its own terms. Van Gogh entered the realm of doctors and asylums after he removed his ear on 23 December 1888. That upsetting story is told with dandy clarity. Here you tin see not only his moving portrait of Dr Felix Rey who saved his life later his horrific human action of cocky-impairment but the petition signed by many of his neighbours in Arles to have this strange, scary, foreign artist locked upwards. Haunting portraits of his swain patients in the aviary include a man with one eye whose status eerily mirrors Van Gogh'south ain i-eared state.

The problem is, the artist'south problems began long before he was diagnosed with mental wellness problems. No one knows to this solar day what precisely his illness was: all the rival theories, from epilepsy to syphilis to schizophrenia, are explored in the exhibition. By concentrating on the period in which he was receiving medical attending, however, information technology implies that before he vicious out with his beau creative person Paul Gauguin in the Yellow House in Arles, Van Gogh was a sturdy rational grapheme of space sobriety. He was "sane", and then became "insane". Actually that is how long-expressionless 19th-century doctors diagnosed him. For a existent agreement of Van Gogh'due south mental health you accept to look much further back in his life and take a pb not from psychiatry but from the novels and paintings he loved.

Above all, you lot have to read his letters. The Van Gogh Museum has published the fullest edition of these outpourings – the most sustained literary self-examination of any creative person – and they reveal a human liable to go overexcited, hugely impractical, formidably intense, often isolated, and incapable to his own sorrow of maintaining happy relationships with women.

Does whatsoever of that make him "mad"? No, but it made him troubled, unhappy, difficult, all his adult life. Our intimate access to Van Gogh's life starts when his letters to Theo begin, when Vincent was in London working for an fine art dealer. He shortly got into trouble: the red-haired lodger in a house in Brixton fell in love with his landlady'due south daughter and made embarrassing declarations to her. And so he left his fine art dealing job, tried teaching, walked across Kent, decided to become an urban missionary and preached a long introspective sermon to baffled suburbanites.

By the time he reached Arles his fiscal dependence on Theo, who had stuck with the art merchandise and was now a dealer in Paris, was unquestioned. No one in his family unit expected him whatsoever longer to get a proper job, or to marry. As a member of the 19th-century suburbia he was a total failure.

Without his brother he would take died in a ditch, or perhaps killed himself much sooner. Van Gogh himself wonders in his letters – before he was ever treated as such by the medical profession – if he is "cracked." The academic faddy for seeing him equally a sensible hard-working creative person who unfortunately became sick at the terminate of 1888 is misplaced. He was ever going off on passionate tangents. What words employ to this homo who could live in conventional society? 1 might be manic. Another might be bohemian.

Van Gogh arrived in Arles from Paris, where he'd completed his long adult education in art and, thanks to Theo'southward contacts, leapt from provincial mature educatee to a fellow member of the avant garde. The artists he encountered and identified with included Toulouse-Lautrec, Seurat and Emile Bernard, who became almost every bit loyal a correspondent equally Theo. There were plans at one point for Bernard, who passionately believed in Van Gogh'south genius, to join him in Arles. In the event it was the far less giving Gauguin who came to stay.

These artists chosen themselves the impressionists of the "petit boulevard" – as opposed to Monet and Renoir, the increasingly successful impressionists of the "grand boulevard" – and saw themselves as revolutionary social outsiders who took every concrete and mental adventure to create a new art. Madness was in the unwholesome air they breathed. Syphilis was one source of danger – Manet had died from it, and one of Van Gogh'southward favourite writers, Maupassant, might lose his reason to it. Insanity was seen as a professional person risk for the modern artist: in his novel The Masterpiece, Van Gogh'due south literary hero Zola portrays an impressionist painter whose pursuit of the new leads to madness and decease. It was published in 1886, 2 years earlier Van Gogh's arrival in Arles. Zola based his doomed character on his friend and former schoolmate Cézanne.

As soon every bit he felt the southern sun on his back, Van Gogh exploded into genius. All he had learned near art through years of difficult work crystallised and he was transfigured. He knew his piece of work was infinitely better than annihilation he had ever done. He also knew he was discovering a completely new style to utilize colour to limited emotion. He painted in bursts of ecstatic creativity: a series of orchards, a nightmarish buffet scene, the exterior of the cafe by night. A series of sunflowers whose colours express joy.

All this assuming experiment, which Van Gogh knew was unprecedented and a unlike way of seeing, was done at huge risk to his wellness and sanity. That is how he tells information technology in his messages. Past the fourth dimension Gauguin arrived that autumn, Van Gogh was exhausted, ready to break.

Was he "mad" when he painted his Sunflowers? Not clinically – at least, his illness had not been diagnosed – but what Van Gogh did in his mature paintings was to channel his capacity for overexcitement into a unique onrush of creativity. What he took from impressionism was the freedom to pigment the colours he wanted. And he found he could live and pigment for days on terminate in a storm, an ecstasy, a dream of colour.

His heroism was non the depressive struggle of a sane human against an utterly subversive illness that this exhibition chronicles. A less myopic look at his art and letters reveals a much more ambiguous dealing with his own dark side. He had a capacity for getting carried away. When he put this into art he created paintings that carry us all away.

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/aug/05/vincent-van-gogh-myths-madness-and-a-new-way-of-painting

Posted by: bursonmich1986.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Were Paints Made For Van Gogh"

Post a Comment